And for today... nothing, 1972

And for today... nothing is the title of an action performed in Part 2 of the exhibition A Survey of the Avant Garde in Britain curated by Rosetta Brooks at Gallery House London in August 1972.

Two previous titles I had appropriated for performances invoked the Labour Party slogan 'You Know It Makes Sense' used in the election of the 18th of June 1970. I was interested in propaganda language used by political parties, in the ways that cliche contains truth while inviting mockery. The title And for today... nothing is not quite the same. It removes thought and feeling, leaving a hole, nothing, an absence that might have been commonly experienced or not. I had been moving in this direction for a number of years since returning to England in 1964. I was an unwilling returnee, then became actively involved on the progressive left which coincided with the emerging political consciousness in the sixties. In 1968 the international aspiration for a greater democracy, a reformist desire which included radical co-conspirators was defeated in Paris and elsewhere.

The title And for today... nothing suggests something of an underlying fatigue in the aftermath.

The action moved the concept to an extreme position, barely breathing just on the water's edge. To live as one breath follows another or entering water to drown.

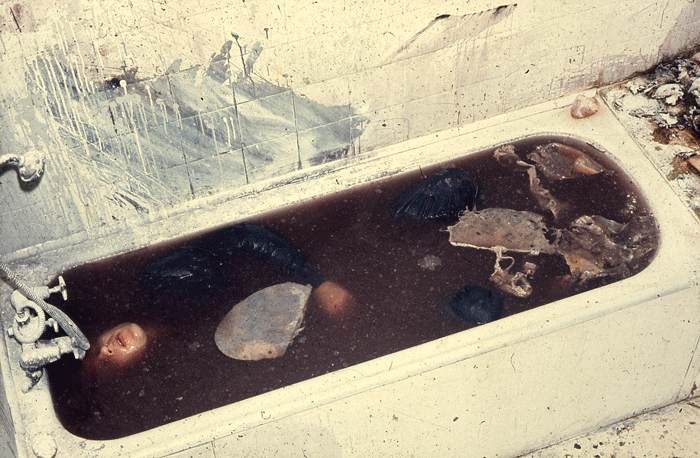

I lay clothed black in a bath of black water.

The ageing white tiled bathroom was partly painted over and paint thrown on the walls in black and white.

The mansion was built in the mid 19th century with the bourgeoisie in mind.

It was not an elegant but a large sturdy property formerly owned by the Mormon Church.

The bathroom I used in this work was on the third floor. A small bathroom with bath and wash hand basin, a window facing south east. There was a shelf with a cupboard under it fitted into the space between the end of the bath and a wall. The bath was fitted against a second wall at right angles to the wall with the door. Looking into the room from the door one would look diagonally right to the head end of the bath with the taps. Next to it on the left at the back was the wash hand basin. The door was left partially open reducing the light level to a sense of twilight.

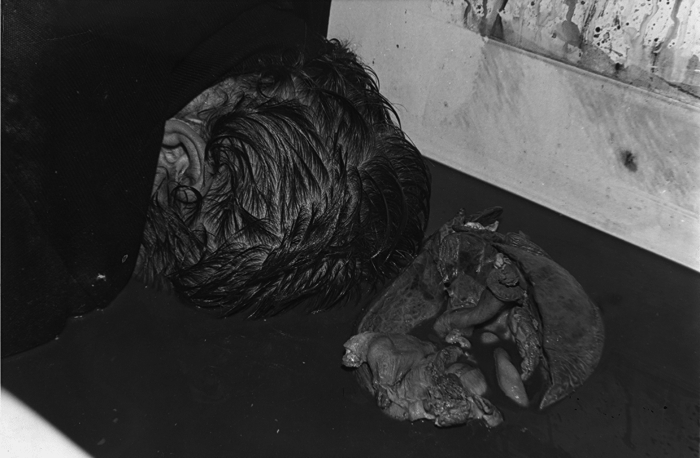

On the shelf at the foot end of the bath was a heap of offal which rotted away during the work. Another pile of offal lay in the wash hand basin, mouldering away. Floating in the bath were unidentified parts closely resembling offal. And there was the stench of rotting offal.

During the two weeks of the performance flies laid eggs on the meat which hatched out into maggots. Those on the shelf at the bottom of the bath migrated into the bath towards the end of the work on one or two days.

Time

I mixed the pigment with the bathwater as hot as I could bear and slipped into it staying until I became so cold that I could not stand to be in it. It took about two hours or so for this to happen. The action was repeated every day for two weeks.

In the water

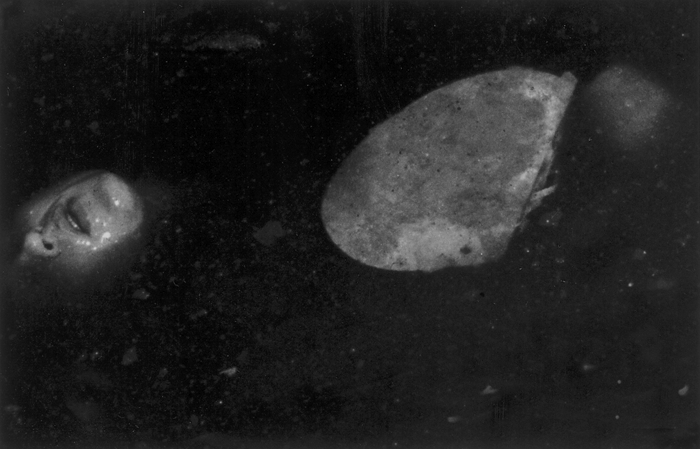

The bath was filled just below the rim. I was immersed just below the surface apart from my head. The water level ran around the head immediately below the nostrils. Breathing in when the body rose up to float, breathing out sinking down establishing the border between water and air.

A Public An Audience

From the initial idea involving the bathroom, I realised that access to this work could only accommodate two or three people at best. Mostly it was one person at a time.

I was often not aware whether there was an audience. I was concentrating on maintaining the balance between air and water. The critical point was around the base of the nose where the body rose and fell in concert with breathing regulating to stop water from entering the nose and allow the gentle tide of breathing to show itself. When the water did enter through the nose it felt like an invasion accompanied by spluttering and coughing which I could not control. The after effect being like a short term sore throat stemming from coughing and the uncontrolled jerky movements. An attentive observer would have seen the barely perceptible movement of the body lying in the bath with the occasional invasion of water through the nose. Of course, I could only imagine what a viewer might see and experience.

Most of the time a single person would be there at the margins of the partly open door. Some stayed in what seemed like an inordinate passage of time passing. Others made cursory glances and left. No one to my memory came right into the room. The audience divided itself into those who stayed, others who left and then some who returned.

I presume that a public who came to see this work would most likely to have been comprised of those informed about Gallery House and contemporary art in general. They behaved privately, coming on their own or in numbers of twos and threes. They were not an audience who came together specifically for a given period of time as is usual for what we call an audience to be and do. They came sporadically each day over a four hour period or so, much as one might visit an art gallery where what is on view is muted until activated by human engagement as visitors. The difference with this live work is the fact that the viewed is much like a tableaux where only the inevitable bodily movement of a person occurs. This work might be described as being non narrative, in so far as what happened was limited more or less, to those inadvertent movements which maintain life i.e. breathing.

The decisive act of behaviour reduction to its bare minimum (almost nothing) is put in place in the bathroom (the scene) so that intended readings of the work can be made.

Stuart Brisley, 2018