I was contracted to work in the Hille furniture factory at Haverhill in Suffolk in 1970.

This was at a time when the production facilities were being enlarged necessitating reorganisation of the factory.

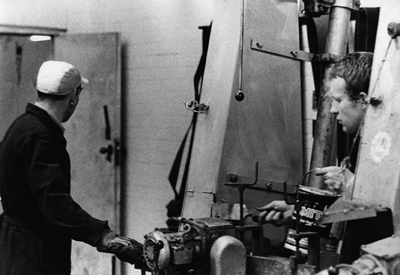

I chose to work in what I thought were the least attractive conditions, the metal polishing room. There were roughly 6 to 8 working stations in the workshop. My intention was to break into communication with the workers and then to extend my contacts across the factory floor. I did manage to gain their confidence and through them learnt about the many ways the factory operated. I did not have any meetings with the union representatives although I know who they were.

I met the factory manager regularly and reported on what I was doing. I was conscious that it was my responsibility to be open and informative both to those on the shop floor and to the management. It is no secret at the time that there were clear divisions between managements and the labour forces across British industry, and that features of the British class system were at work together with the characteristics of the basic education system at the time. It was my intention to speak to all this and to formulate methods to extend communication between the various aspects of shop floor working (where the work is done) and then to institute places and facilities where the shop floor/ and management could communicate with each other largely through text.

As in institutions in general there will always be questions arising when misunderstanding takes place. So firstly as above, I gained the confidence of the metal polishers and did not break that trust by reporting on what I found to management unbeknown to them. I did not see myself as either as a management or workforce tool. I asked the metal workers that the efficiency of the metal polishing could be improved. They showed how inefficient the system actually was. I asked if they had spoken to management about it. They said management rarely spoke to them. They were contemptous of the sighting of windows well above the eye level which was in their view intended to limit what they could see in order to get them to stick to their work. Their preception that this was an ugly element of management control prohibited them from communicating with management at all unless spoken to. It may seem like a small thing in itself but this defined the state of an undeclared conflict present. I asked them about educational opportunities which might be available and encouraged two of them to find out more which they did. They were acutely aware of the limitations and the fragility of their employment which coloured their views of factory life.

The 3 elements of my placement were:

1. I painted the machinery in the workshop to the various football team colours the workers supported. This was a means of identifying with the workers.

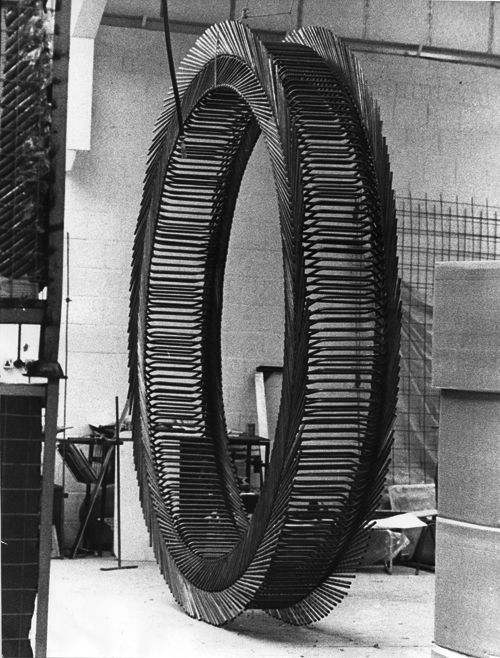

2. The wheel - made out of 212 chair frames representing the continuity of the factory belt which was a closed movement. The chair frames when stacked naturally curved and revealed a closure. To the worker on the factory line it is a reflection of the nature of the work - labour without an end. You might as well be the mouse on the treadmill going round and round.

3. I instigated notice boards across the workshops for workers use. These were used for all sorts of communication including sports activities, exchange and sale of goods, social notices, grievances etc.

Stuart Brisley

February 2013

Please go to the Text section for further documentation:

APG/Hille Project: Report on APG artist's visit to Hille factories

Letter between Barbara Latham and Leslie Julius regarding Hille Project

Letter between H.J. Hammonda and Barbara Latham regarding Hille Project

Hille Fellowhip – Factory and Artist: The Industrial Context

Report on APG Project at Haverhill, September 1970 – March 1971

The Artist and Artist Placement Group / Studio International

The account of the Hille Project by Barbara Steveni/APG Administration, 1998